Report on  Program

Program

September 27, 2006

John T. Whitehead, Ph.D.

Dept. of Criminal Justice & Criminology

East Tennessee State University

Report on Moral Kombat

Fall 2006

Introduction

![]() is an ethics-based restorative justice program run by the First Tennessee Human Resource Agency. Initially, the program focused on character education and ethical behavior training for older, troubled, at-risk youth. The program consists of six 2-hour sessions about universally accepted values and ethical decision-making skills (program website: www.fthra.org).

is an ethics-based restorative justice program run by the First Tennessee Human Resource Agency. Initially, the program focused on character education and ethical behavior training for older, troubled, at-risk youth. The program consists of six 2-hour sessions about universally accepted values and ethical decision-making skills (program website: www.fthra.org).

More recently, ![]() has expanded to include training in parenting, emotion control, life skills, dealing with drug and alcohol abuse, and a program to combat theft, shoplifting, and bad check writing. It has also expanded to include adults as well as adolescents.

has expanded to include training in parenting, emotion control, life skills, dealing with drug and alcohol abuse, and a program to combat theft, shoplifting, and bad check writing. It has also expanded to include adults as well as adolescents.

Current Evaluation

Data was collected on approximately 450 youths who were in the ![]() program from July 1, 2003 through June 30, 2004. Unfortunately, data on the recidivism of several hundred additional youths who went through the program was not available. Researchers went to the courthouses and were unable to determine whether or not if these latter youths had committed new offenses. (Most of the tables below were based on 455 youths for whom the relevant information was available. Missing information resulted in some of the tables having slightly different sample sizes (Ns) and/or percentages.)

program from July 1, 2003 through June 30, 2004. Unfortunately, data on the recidivism of several hundred additional youths who went through the program was not available. Researchers went to the courthouses and were unable to determine whether or not if these latter youths had committed new offenses. (Most of the tables below were based on 455 youths for whom the relevant information was available. Missing information resulted in some of the tables having slightly different sample sizes (Ns) and/or percentages.)

One reason for lack of follow-up information on some youths was the fact that they turned 18 before the end of the fiscal year. Information simply was not available for those students.

However, a sample size of over 400 youths does allow us to place considerable confidence in the findings. It also allows for breakdowns such as comparing male and female youths who participated in the ![]() program.

program.

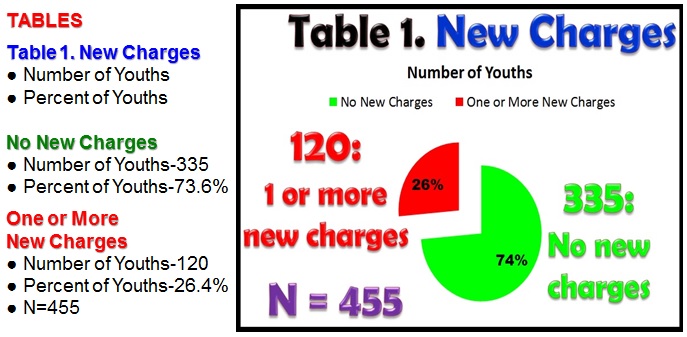

Overall, the vast majority of youths who received ![]() training did very well. Specifically, almost three-quarters (74 percent) of the youths who completed the program succeeded; in other words, they did not commit a new offense. Conversely, only about one quarter (26 percent) of the youths who completed

training did very well. Specifically, almost three-quarters (74 percent) of the youths who completed the program succeeded; in other words, they did not commit a new offense. Conversely, only about one quarter (26 percent) of the youths who completed ![]() failed by committing a new offense. (See Table 1.)

failed by committing a new offense. (See Table 1.)

Furthermore, an analysis that omitted 10 youths from the failure category because their charges were marked "traffic" or "withdrawn" showed that 77 percent of the youths succeeded and only 23 percent failed. So the 74 percent success rate is a conservative estimate.

Another encouraging piece of news is that there were not many serious charges for those youths that did commit another offense. Most of the first charges against reoffending youth were minor. Thirty-six (36) youths or 30 percent of those with a first new charge simply committed some violation of their court order or probation. One dozen youths (10 percent) committed some form of theft and another twelve (10 percent) were charged with a tobacco violation such as underage possession of tobacco.

The most frequent serious charge was some type of assault charge. Fourteen (12 percent) of the first charges were some type of assault charge. Concerning the first charge only, one youth was charged with Second Degree Murder, one with vandalism over $60,000, and four were charged with reckless driving, reckless endangerment, or leaving the scene of an accident. Only sixty youths were charged with a second offense. For such youths charged with a second offense, again the offenses tended to be minor. The most frequent charge for these youths was Violation of a Court Order or Violation of Probation: 23 youths (38 percent) were charged with such Violations. Five youths (8 percent) who had a second charge were charged with a tobacco violation such as underage possession of tobacco. Only six youths (10 percent) with a second charge were charged with aggravated assault or assault. The rest of the second charges were quite varied: leaving the scene of an accident, possession of a weapon, possession of alcohol, speeding, theft, and truancy.

Only 13 youths committed a third offense. Over half of these (7/13) were clearly minor offenses such as traffic charges, unruly, disorderly conduct, and vandalism.

Only 9 youths committed a fourth offense. Only two of these appear serious: one assault charge and one charge of leaving the scene of an accident with injuries.

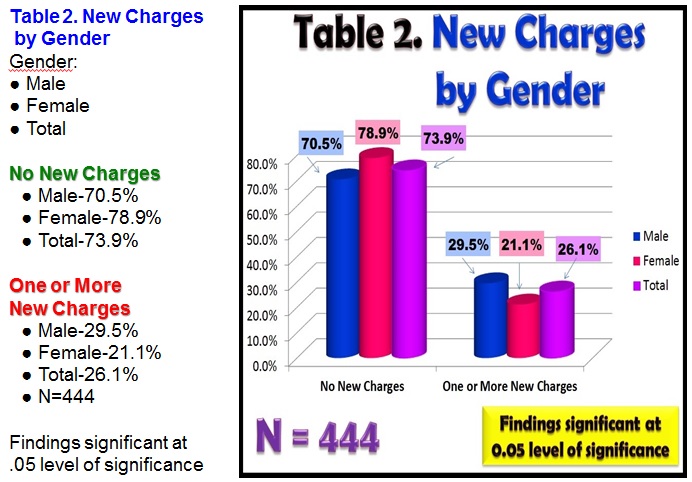

There was a gender difference in outcomes (see Table 2.) A slightly higher percentage of females, 78.9 percent, succeeded compared to males, 70.5 percent. This gender difference was statistically significant but weak. It was just barely significant at the .05 level of significance and phi was under .10 which is as weak as you can get and still be significant. (Phi is a measure of the strength of a relationship.)

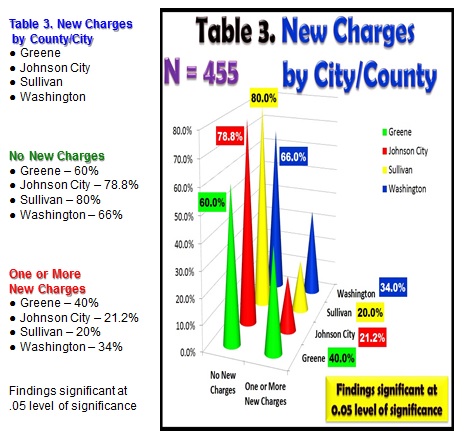

City or County of referral was also a significant correlate of success/failure (see Table 3).

Sullivan County youths had the highest success rate: 80 percent; followed by Johnson City, 78.8 percent; Washington County, 66.2 percent; and Greene County, 60 percent. Thus, there was approximately a 20 percent difference between Greene County and both Sullivan County and Johnson City youths. Still, it must be cautioned that even in Greene County, a majority, in fact 60 percent, of the youths succeeded. So, the program was successful with all youths regardless of city/county of referral.

Which specific administration of the program the youth attended was not a significant correlate of success.

Conclusion

Almost three quarters of the youths (about 75 percent) who went through ![]() training remained crime-free. Only about one-quarter committed a new offense. Furthermore, many of the new offenses were minor offenses.

training remained crime-free. Only about one-quarter committed a new offense. Furthermore, many of the new offenses were minor offenses.

Although lack of an experimental design with random assignment and a control group makes it impossible to definitely attribute this success to the ![]() program, it is encouraging that such a high percentage of

program, it is encouraging that such a high percentage of ![]() youth succeeded.

youth succeeded.